Date:2025-12-08 09:25:41

According to Kennesaw State University, internal structures of 3D printed components often limit strength and reliability. New research from the university shows that adjusting build settings can significantly improve part performance, making a printed component nearly three times stronger and offering a pathway toward safer and more efficient designs.

Under the guidance of Department of Engineering Technology Assistant Chair Aaron Adams, mechatronics engineering student Eric Miller is exploring how internal structural features influence performance in critical applications such as nuclear energy. As a member of KSU’s START Lab within the Southern Polytechnic College of Engineering and Engineering Technology, Miller collaborates with students and faculty focused on simulations, additive manufacturing, and advanced materials research.

Their project, supported by the Summer Undergraduate Research Program and the Sophomore Scholars Program, explores how small design choices affect the strength of 3D printed parts. Adams said the work could help solve longstanding challenges in nuclear fuel efficiency. “Right now, the fuel is in the form of a pellet about the size of a penny, and the pellets are stacked together like a roll of coins,” said Adams, an associate professor of mechanical engineering technology. “These fuel pellets are then placed inside a fuel rod. When the nuclear reaction begins, they heat up, expand, and come into contact with the rod wall. Because they have no room to expand, they must be removed before the fuel is completely depleted, limiting how much of the fuel can be used. Ultimately, we hope to achieve a 15 percent increase in fuel utilization using complex geometries.”

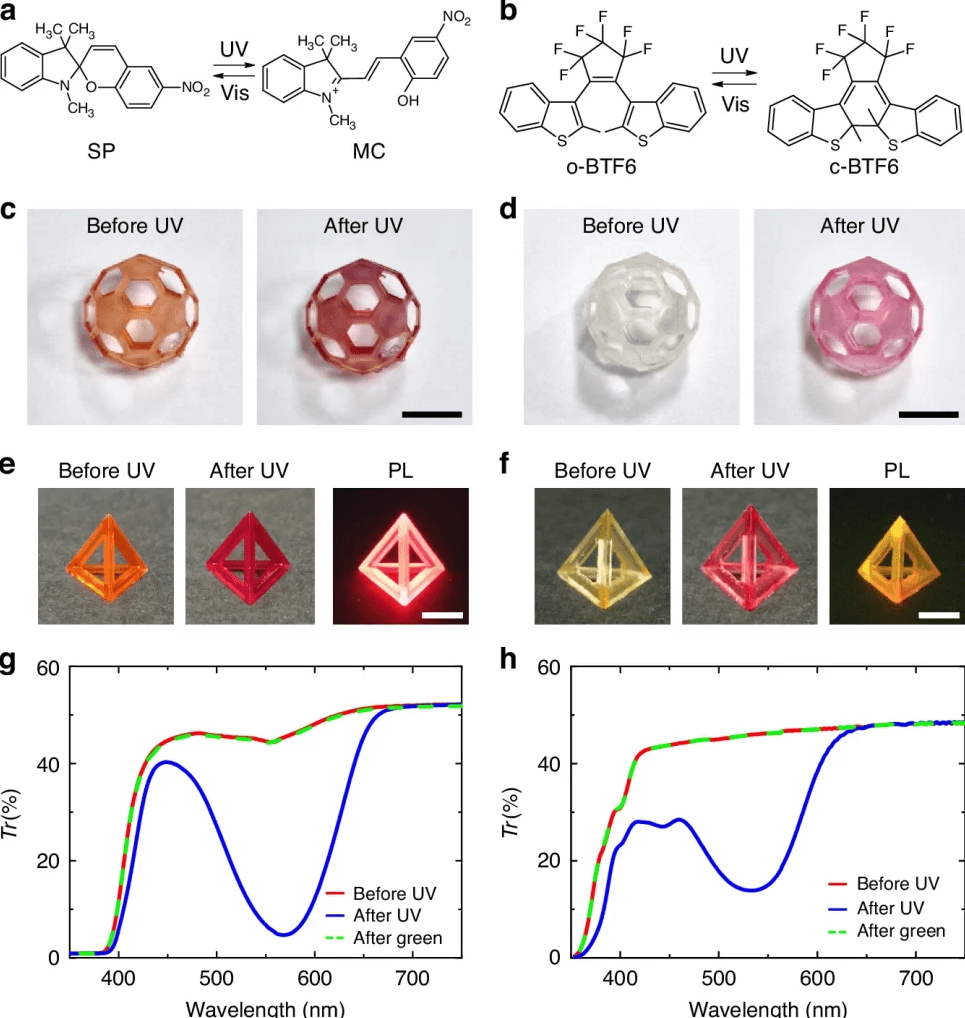

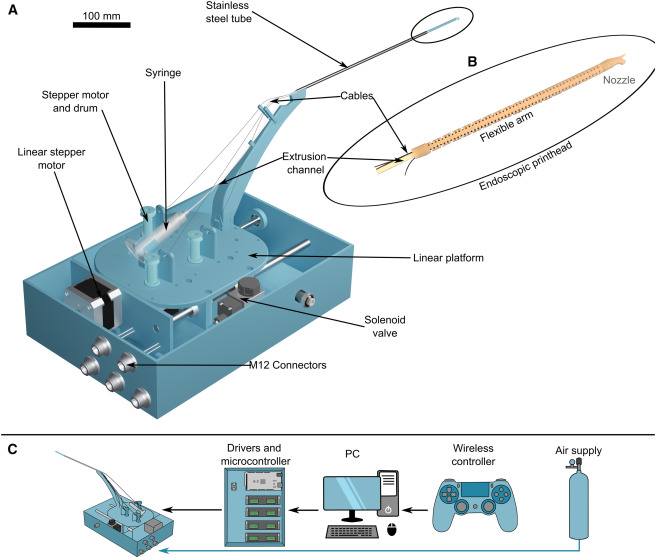

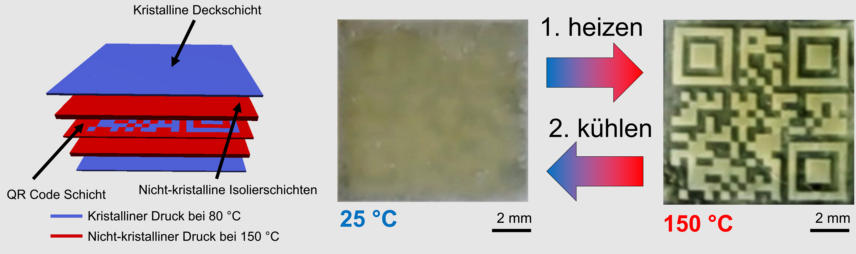

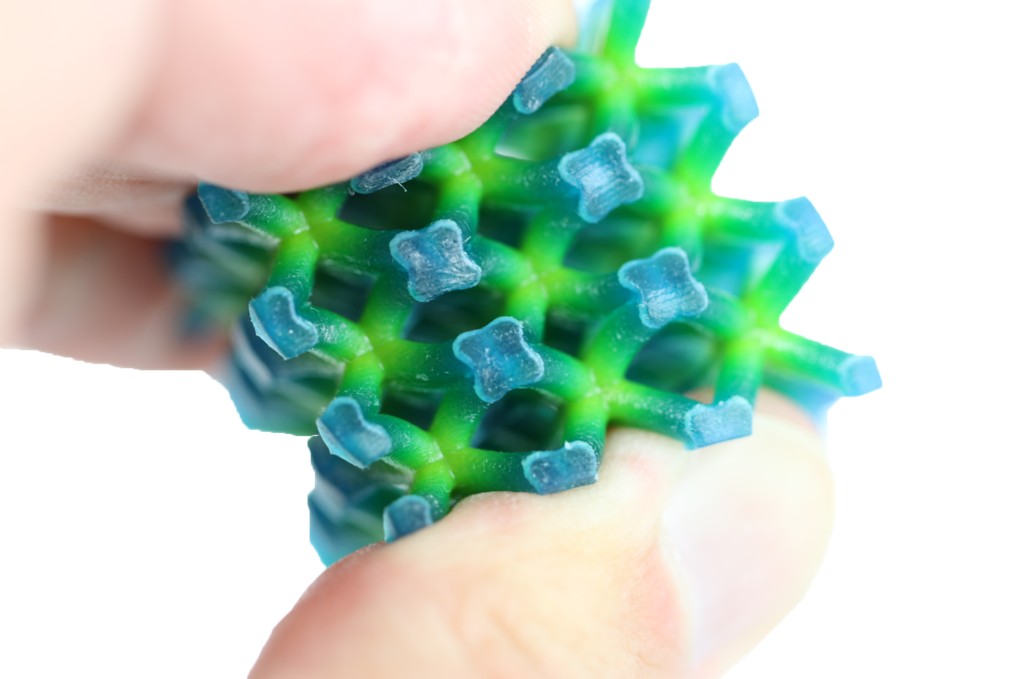

The team is studying how 3D printing can create internal channels and new lattice structures that give the material room to expand, thereby increasing both efficiency and safety.

Miller’s role involves designing models, preparing simulations, and utilizing Finite Element Analysis (FEA) to test various combinations of lattice angles and densities. He mentioned that the work pushes him beyond the scope of his typical mechatronics coursework and has enhanced his understanding of mechanical behavior.

“I wanted to get more into the mechanical engineering world because we focus less on that in mechatronics. Getting into strength of materials and FEA has been a great learning experience,” said Miller, who added that the accessibility of 3D printing has always fascinated him. “When I was younger, I was kind of clumsy and would break things all the time. Using a $200 printer and free software, I’ve been able to make replacement parts for things I’ve broken. It really lets me imagine something and then build it at home, even if it’s not as complex as nuclear fuels.”

Running extensive simulations has also presented challenges. The detailed mesh sizes needed for curved geometries have pushed the limits of the lab’s computing resources, an obstacle Adams sees as part of the educational process. “If you sum up our biggest challenge in one word, it’s resources, specifically our ability to run highly computational simulation models,” he said. “But I give Eric the task, and he runs with it. He always exceeds expectations.”

“This is the kind of real-world research we champion,” said SPCEET Dean Lawrence Whitman. “Eric and Dr. Adams are developing solutions that contribute to national energy security and strengthen the future of manufacturing.”

Miller will present the Kennesaw State University team’s findings at an upcoming American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) conference.