Date:2025-12-22 10:08:21

Artificial intelligence is learning to stop hogging the driver’s seat in scientific discovery.

As “self-driving” laboratories grow more common, researchers have debated whether machines should fully take over experimentation or merely assist human scientists.

A new study from Argonne National Laboratory and the University of Chicago suggests a third way where humans and AI actively share control.

The research introduces an “AI advisor” model designed to guide, not dominate, autonomous labs.

Instead of locking experiments into a single algorithmic strategy, the system continuously analyzes results and flags moments when human judgment could improve outcomes.

Developed by a team led by UChicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering Assistant Professor Jie Xu, who also holds a joint appointment at Argonne, the model borrows ideas from software used in financial trading.

The AI crunches data in real time, while experienced researchers retain authority over strategic decisions.

Xu said the advisor constantly evaluates how well the lab is performing and alerts scientists when a shift might be needed.

“The advisor will perform real-time data analysis and monitor the progress of the self-driving lab’s autonomous discovery journey,” Xu said.

“If the advisor observes a decline in performance, the advisor is going to prompt the human researchers to see if they want to switch the strategy, refine the design space or so on.”

Sharing the driver’s seat

Unlike traditional autonomous labs that follow a fixed plan from start to finish, the advisor-driven system adapts as experiments unfold.

Xu said this flexibility “makes the entire decision workflow adaptive and boosts the performance significantly.”

Co-corresponding author Henry Chan, a staff scientist at Argonne’s Nanoscience and Technology division, emphasized that the goal is not to choose between humans and AI.

“But here we’re taking a cooperative approach where humans can play a role in the process also,” Chan said.

“We want to facilitate the collaboration between human and AI to achieve co-discovery.”

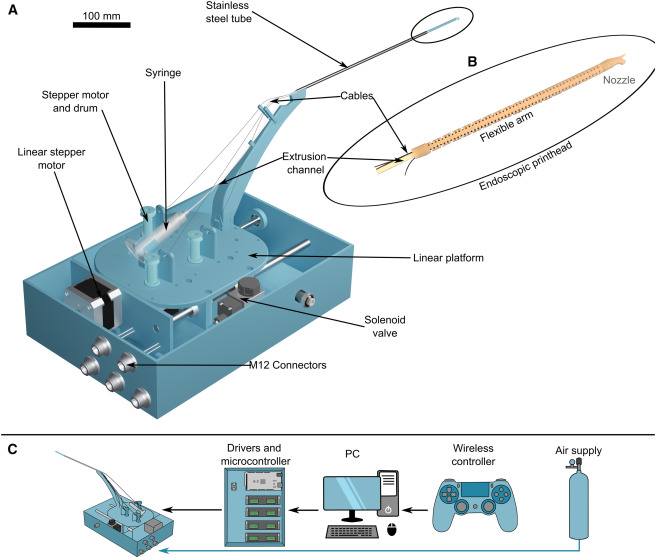

To test the model, the team deployed it in Polybot, a self-driving lab at Argonne’s Center for Nanoscale Materials.

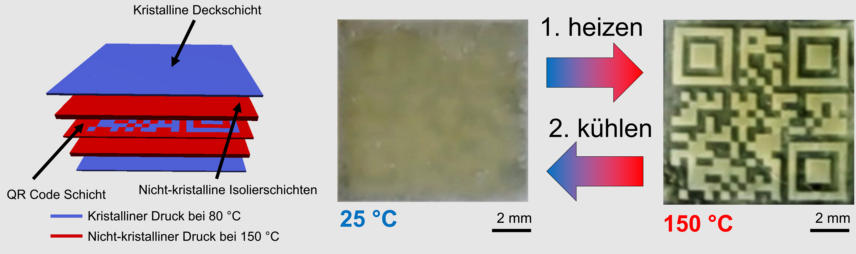

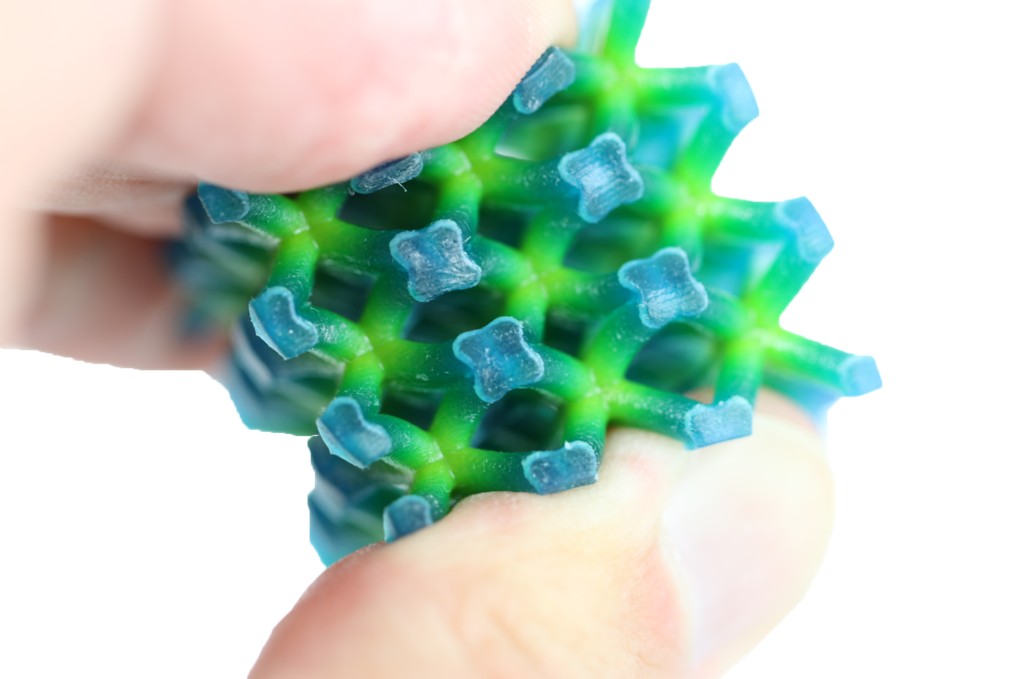

The system was tasked with designing a mixed ion-electron conducting polymer, or MIECP, used in electronic materials.

The results were striking. Materials developed with the AI advisor showed a 150 percent increase in mixed conducting performance compared to those produced using previous state-of-the-art methods.

When humans still matter

Beyond performance gains, the advisor also helped researchers uncover why the material improved.

The system identified two critical factors behind the boost in volumetric capacitance: larger crystalline lamellar spacing and a higher specific surface area.

UChicago PME Associate Professor Sihong Wang said this dual achievement—better performance and deeper understanding—is crucial for materials science.

“For material science research, there are two intercorrelated goals,” Wang said.

“One is to improve the material’s performance or develop new performance.”

She added that the second goal is understanding how design choices shape results.

“By making the entire space of the structure variation much larger, this AI model has helped to achieve two goals at the same time,” Wang said.

The researchers argue that AI still struggles when data is sparse, a scenario where human intuition remains valuable.

“While AI is excellent at this form of data analysis, it falters at decision-making when there are few data points to guide it,” Xu said.

Looking ahead, the team hopes to deepen the two-way interaction between humans and machines.

“In the future, we want a tighter integration between AI and humans,” Chan said, where AI can learn directly from human decisions and refine its own reasoning.