Date:2026-02-05 15:54:13

Mechanical engineers at Duke University have developed solid building blocks whose mechanical properties can be programmed and reprogrammed on demand.

By controlling whether tiny internal cells are solid or liquid, the blocks can change stiffness, damping, and movement without altering their overall shape.

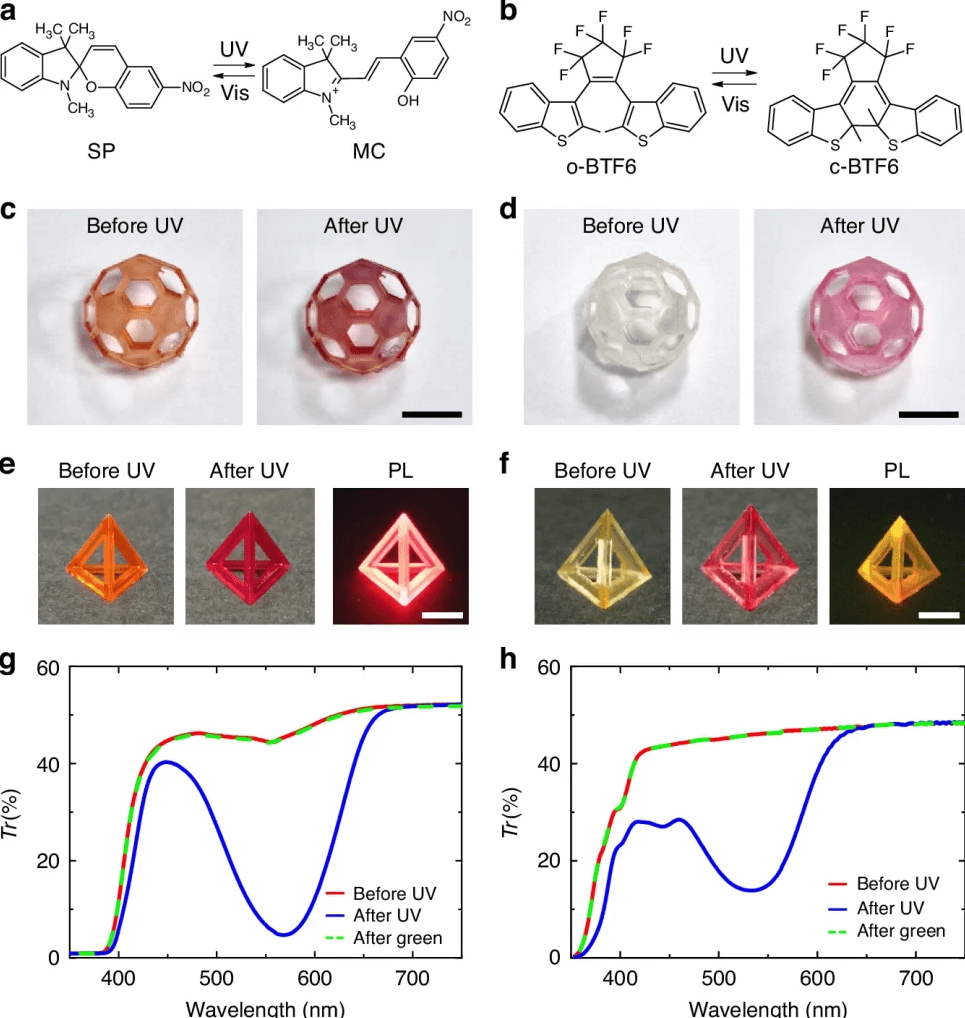

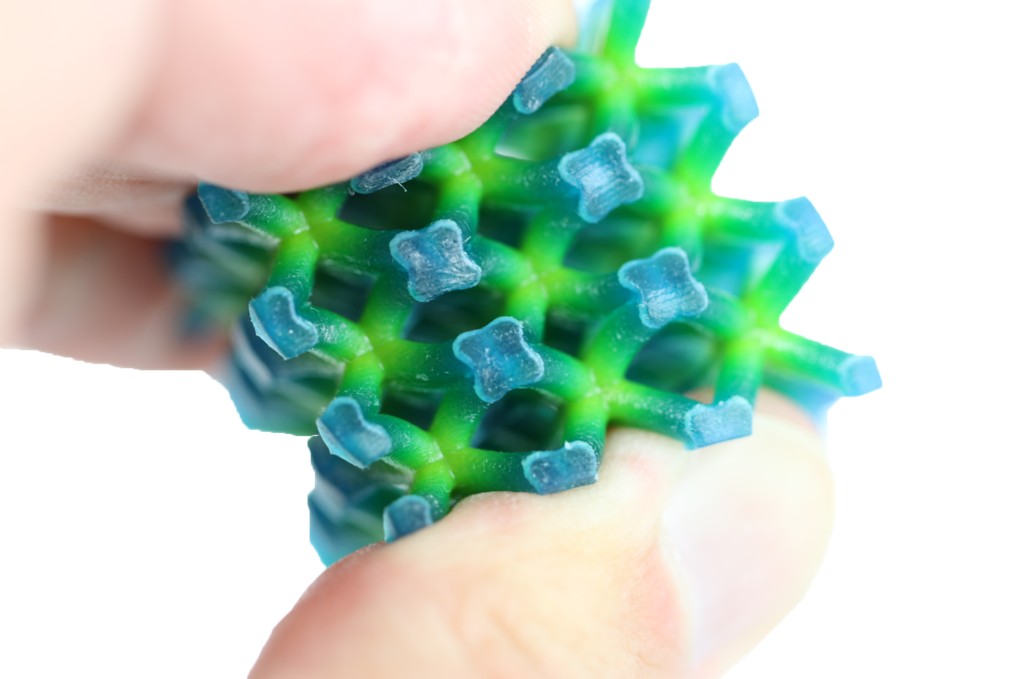

The proof-of-concept uses Lego-like cubes made of 27 internal cells each. Every cell contains a gallium-iron composite that can switch between solid and liquid states at room temperature.

By applying localized heat through an electrical current, researchers can liquify specific cells in precise patterns, effectively encoding mechanical behavior into an otherwise rigid structure.

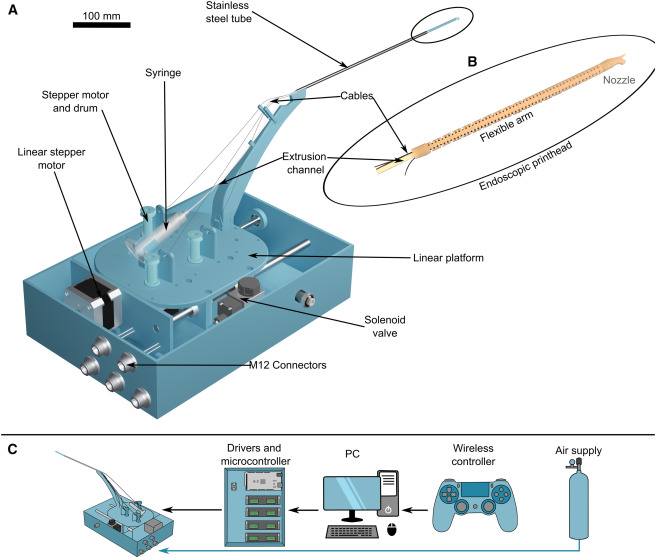

In early demonstrations, the team assembled multiple cubes into beams and columns whose bending and vibration behavior changed based solely on which internal cells were liquified.

The same structure could behave like soft rubber or stiff plastic without being rebuilt or reshaped.

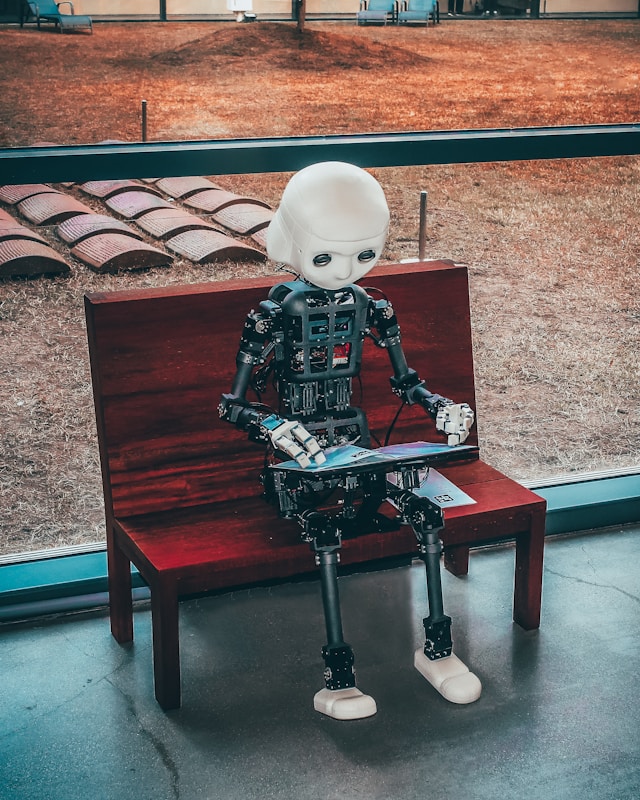

The most striking demonstration came in water. Researchers assembled 10 cubes into a straight column to act as a programmable tail for a robotic fish.

Using the same motor input, different internal configurations caused the fish to swim along sharply different paths, showing how motion can be altered through material programming alone.

Materials that act alive

“We want to make materials that are alive,” said Yun Bai, first author on the study and a PhD student at Duke. “3D printers can create materials with specific mechanical properties, but you have to repeat the print to change them. We wanted to create something like human muscles that can change their stiffness in real time.”

Unlike shape-shifting materials, the system changes mechanical response without changing geometry.

In two-dimensional tests, the researchers showed that thin sheets could precisely tune stiffness and damping while maintaining the same form factor. These sheets were tested against commercially available materials and demonstrated a wide performance range.

In three dimensions, the modular nature of the blocks adds another layer of flexibility.

Each cube can be attached or detached like Lego bricks, allowing engineers to assemble larger systems with highly customized mechanical behavior. Once a configuration is tested, freezing the structure at zero degrees Celsius resets all cells to a solid state, enabling repeated reprogramming.

Rewriting solid mechanics

“This gives us the flexibility to create 3D structures with different mechanical properties,” Bai said. “And freezing the blocks at zero degrees resets all the cells to their solid state so that their configuration can be reprogrammed again and again.”

Beyond robotics, the team sees potential applications in medicine and electronics. By adjusting the metal composition, the freezing and melting points could be tuned for environments such as the human body.

Miniaturized versions could one day navigate blood vessels, monitor health, or reconfigure into adaptive stents that respond to changing conditions.

“Our goal is to eventually construct larger systems using the composite materials,” said Xiaoyue Ni, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at Duke.

“We want to build flexible, programmable materials for robotics that can enable them to perform a wide variety of tasks in a wide variety of environments.”